Into the Archives with Nora Krug: The Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies

On November 14, SCVN Research Assistant Lucie Kotesovska met with Nora Krug, an internationally acclaimed artist and illustrator and author of several book-length visual narratives. Nora is currently an artist-in-residence at Yale’s Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, where she is conducting research of the survivors’ video and written testimonies. Her aim is to produce a graphic novel based on her engagement with these archival sources.

In this interview, Nora spoke about her current research and how she envisions the form of her next book. She also shared her thoughts on the unique potential of the visual narrative when communicating survivors’ experience and whether it is ever possible to overcome the trauma of war.

Lucie: Can you tell us a little bit about your current research and your research method as you work with the materials at Yale’s Fortunoff Video Archives, and also, how do you envision the final product at this point?

Nora: I’m only just embarking on the research for the book. I haven’t fully figured out the themes yet, but roughly speaking, I think it will be about the question of resistance and forgiveness, and whether we can ever overcome political trauma, personal trauma, and retaliation, all of these aspects. I’m researching the testimonies of survivors that were recorded in the 70s and 80s that touch on these subjects. I’m watching the interviews and I’m looking for certain keywords. I’m finding it difficult to find certain information, especially when it comes to description of violence. It’s a taboo, for instance, to talk about violent acts that you might have been involved with during the resistance. That’s an interesting component, but also something that’s hard to track down at least based on what I’ve encountered so far. I’m eager to look at both men’s and women’s testimonies from various different countries. I’ve watched some in Hebrew—there’s often a transcription in English—some in German, some in Polish, some in English. It’s interesting to observe how differently people dealt with the legacy of trauma, of experiencing trauma. People experienced it in different ways and had different modes of survival. I’m interested in that too—what makes us respond to certain traumas in different ways. And while I’m doing this, I’m also doing some research outside.

From top left: Cassette tape, files, and VHS tapes from the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. Photos courtesy of Stephen Naron and Nick Porter.

I would say when I embark on research, I’m not extremely systematic, I’m rather very broad. And I try to articulate the basic underlying questions that I’m asking myself for a new book project. I’m not interested in telling a story chronologically, you know, the story of one person’s life. While the testimonies are very gripping and emotional, I’ve decided not to focus on one person’s life, and not to tell a chronological story but rather approach universal themes that I find in the interviews and create a sort of collage of my own thoughts on that subject that will include individual narratives. For instance, my book Belonging was structured in this way: I interwove several different narratives in a kaleidoscopic way. So, I think that’s what I’m envisioning at the moment—including different voices. I would also like to branch out after this year at Yale to other crimes, other wars, other cultures, and other religions, so that the subject of the book won’t entirely focus on the Holocaust, but also on how we deal with these experiences universally.

I’m not interested in telling a story chronologically, you know, the story of one person’s life. While the testimonies are very gripping and emotional, I’ve decided not to focus on one person’s life, and not to tell a chronological story but rather approach universal themes that I find in the interviews and create a sort of collage of my own thoughts on that subject that will include individual narratives.

Now that I’m at Yale, I’ve been connecting with professors from different departments including the Visual Arts Library, the Beinecke Library, and the Psychiatry Department, to get different people’s input into these questions. I also found a photo album at a flea market in Berlin some years ago that belonged to a German soldier. He documented an atrocity committed by the German Wehrmacht in Poland in 1939. I had this album lying around for many years thinking about what I could do with it, how to make those important photographs accessible to the public. And I would like to find a way of integrating it into the narrative of this new project. So, I’ve been reaching out to historians in Poland, the United States, Germany and Austria, to get more information about the historic events surrounding the atrocity depicted in this album, and to try to find out who the people depicted in the photographs are.

From Left to right: Card catalog cabinets, video library and VHS tape from the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies. Photos courtesy of Stephen Naron and Nick Porter.

Lucie: It sounds as if you anticipated my next question and, in a way, already answered it. In the SCVN team, we have been wondering whether you plan to focus on one main story or several of them in your next book project. Could you talk a bit more about how you envision working with multiple narratives?

Nora: Yes, I’m trying to look at my work less as illustrated biography and more as a philosophical reflection on themes that could include multiple narratives, also contradicting ones. This was the case in my last book, Diaries of War, about Ukraine and Russia, where I portrayed the voices of a Ukrainian woman and a Russian man, and even though the Russian man was anti-Putin, it is a contradictory narrative, and it clashes with the perspective of the Ukrainian protagonist. What I’m interested in as an artist and a writer is to bring out the complexities and the subtleties and focus on narratives that can be difficult to confront, because they’re uncomfortable or because they don’t fit into our conventional understanding of war or of the Holocaust.

What I’m interested in as an artist and a writer is to bring out the complexities and the subtleties and focus on narratives that can be difficult to confront, because they’re uncomfortable or because they don’t fit into our conventional understanding of war or of the Holocaust.

Lucie: This leads me to another question. In your understanding and in your practice, what do you see as particular strengths of the visual narrative when dealing with trauma and the topics that you mention?

Nora: For me, it’s very important to recognize the whole political history of illustration as a medium. It’s always been a political medium. It was the only visual medium that communicated political and social ideas before the advent of photography. We tend to forget that now. It is a political tool that shapes the way we think and feel or that hopefully opens up new perspectives because it is so visceral and so direct. And it can provide a very direct emotional entry point into narratives about war and memory and history in a way that I think classic textbooks aren’t able to. We understand that with movies—with movies, there’s no question. I mean, fiction films about the Second World War are very emotionally gripping, but with illustrated narratives, the general population wouldn’t necessarily recognize that medium as a powerful tool in the same way. I don’t know why that is given that for centuries it was such an important tool. I mean, if you think about illustrated church manuscripts, but also illustrated representations in other religions and cultures—illustrations were always used to inform the way we think about the world, but also to propagate, for instance, stereotypical ideas like antisemitic depictions in the Middle Ages.

So, while I really appreciate the political strength of the medium, I’m also aware that you have to treat the medium very sensitively and responsibly as an artist. I thought about that a lot when it comes to the depiction of violence. I’m somebody who really feels that it’s important to not avoid violence in images because we need to know what happened, for instance, during the Holocaust. If there hadn’t been any photographs taken at the time when the camps were liberated, our understanding of the Holocaust would be so much more limited. So, I think I’m really a proponent of showing images, of witnessing historical events, even if they’re hard to look at. But at the same time, there are many different ways of representing violence as an illustrator. It’s more a question of how rather than if you should show violence. But that is a component I think about a lot—what’s my responsibility as an illustrator to illuminate these subjects without being voyeuristic or sentimental. It’s sometimes a very fine line.

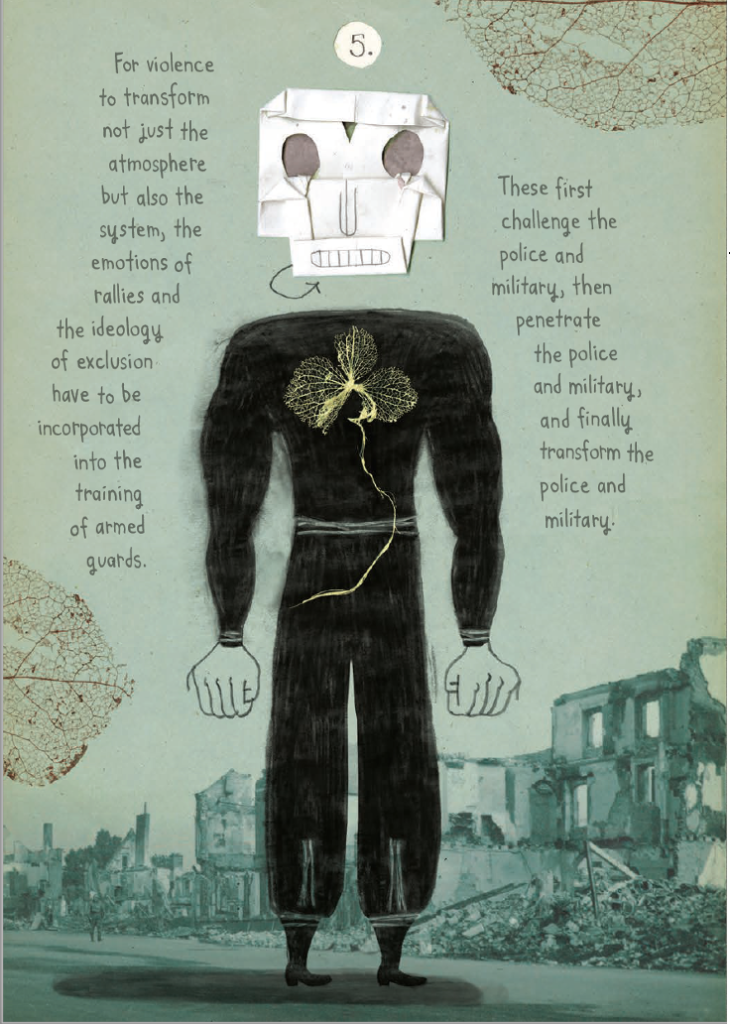

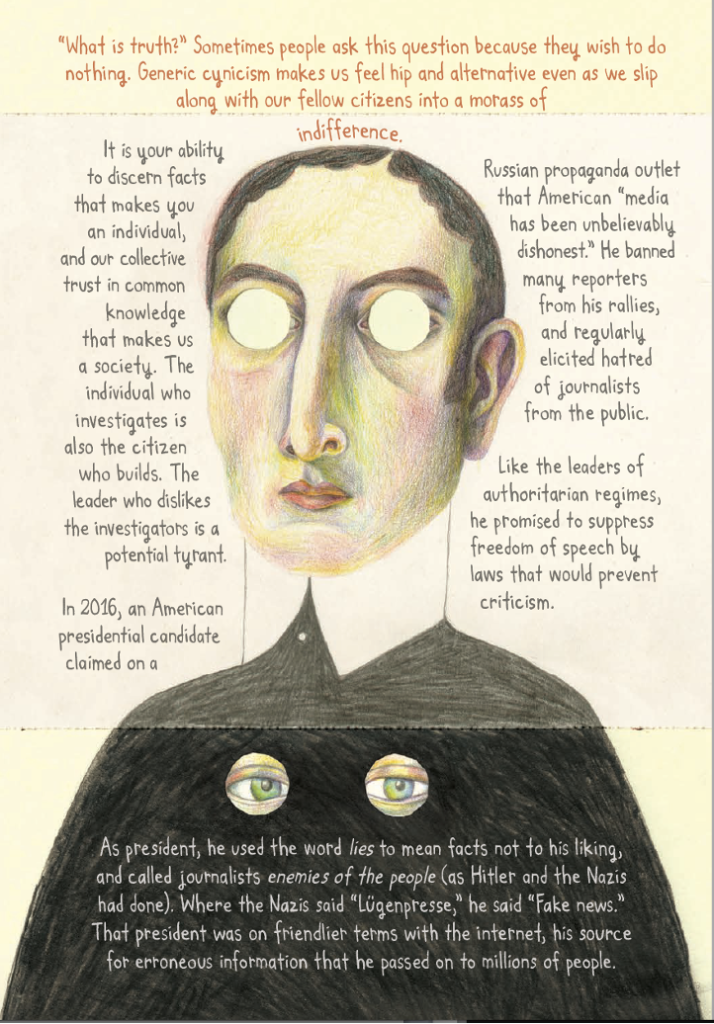

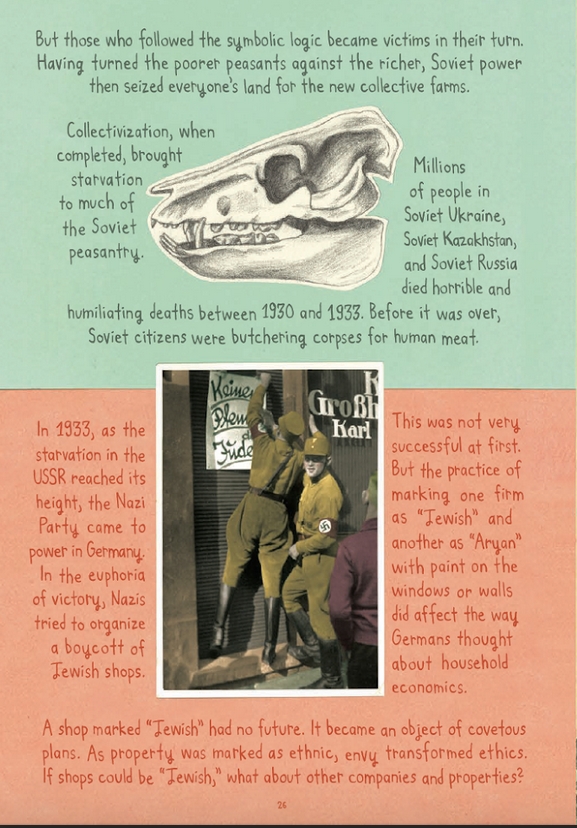

Illustrations from ‘On Tyranny Graphic Edition: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century’ by Nora Krug and Timothy Snyder, 2021.

But at the same time, there are many different ways of representing violence as an illustrator. It’s more a question of how rather than if you should show violence. But that is a component I think about a lot—what’s my responsibility as an illustrator to illuminate these subjects without being voyeuristic or sentimental. It’s sometimes a very fine line.

Lucie: You mentioned that as a researcher and illustrator working with the trauma of war and mass atrocities can be extremely challenging. Can you speak a little bit about how this might affect you, and also how do you take care of yourself during this process?

Nora: Unfortunately, I don’t reflect enough on how I should take care of myself, because I always focus on my sense of responsibility of dealing with these subjects rather than on how my research will make me feel. I think my curiosity is what drives me forward despite the difficulty of the subject matter. When I wrote Belonging, a lot of people said, oh, that was so brave. I never thought of it as brave. I always felt like I simply had to find out what happened. I had such a burning desire to understand war and why people fight wars and how we live with the trauma of war that everything else was pushed into the background. I know that’s problematic because I also do a lot of visual research and looking at those photos probably impacts me emotionally on some deep level.

As illustrators, we have to do a lot of visual research, which means you look at photographs of the Warsaw ghetto or other atrocities throughout history. I try to switch into a professional mode when I do that, but it probably weighs on me in ways that I’m not always aware of. At the same time, making books on these subjects is my way of dealing with all the terrible things that are happening in the world. It’s my way of staying sane because there’s a lot of anger, a lot of anxiety about what’s going on. And I feel like confronting this directly is my preferred way of handling those feelings. So, it’s in a way therapeutic, even though it can be challenging. But I probably should find better ways of dealing with the emotional repercussions.

Lucie: The archival work, which you engage in at the moment, is quite unique within the Survivor-Centered Visual Narrative project. Is archival work also new to you? And what differences do you see between this kind of work and listening to survivors face to face?

Nora: I’ve done a lot of archival work. I did a lot of archival research for Belonging when I was looking for my grandparents’ files from the time of the Nazi regime. I went to the local archive in my father’s village and looked at the police documents from between 1933 and 1945. I looked at some of the letters that were written after 1945 by Jewish emigres who wanted to know what happened to their houses and their property. So, I’ve done a lot of research in archives, not academic research, but research to look for personal narratives. I love that. I find it so exciting to stumble across these voices that would otherwise remain unheard and then bring them back to life. One thing that I find a bit challenging is that the interviews I’m watching are with people who have already passed away, so I can’t ask follow-up questions. Sometimes I have very different questions than the ones that the interviewers ask. That’s a challenge that I’m experiencing because I’m not the one asking the questions.

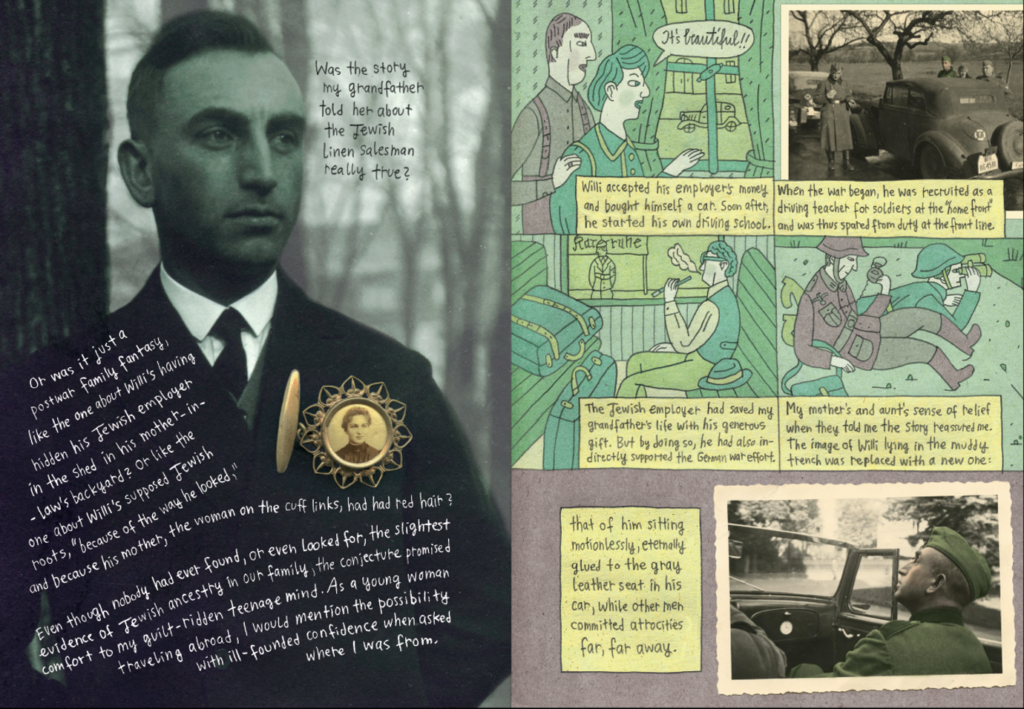

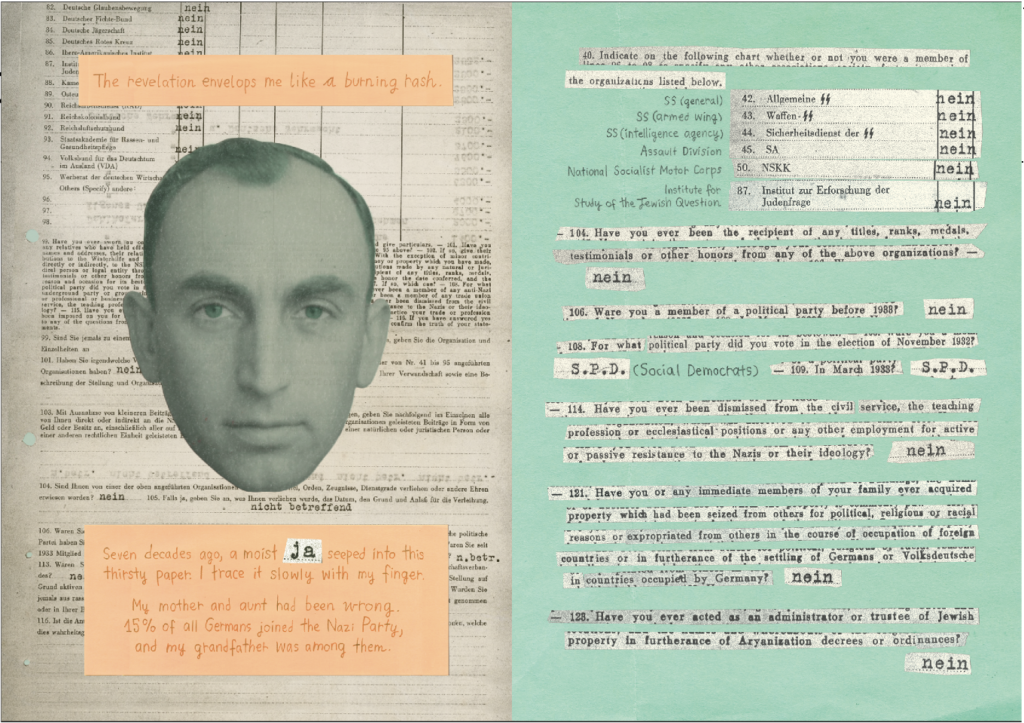

Pages from Nora Krug’s ‘Belonging: A German Reckons with History and Home’, 2018.

A lot of the questions that are asked in these interviews are about the chronology of what happened where they were born, how they experienced anti-Semitism as a child, when they had to flee or hide or what camp they were in, how they escaped or how they survived. All of that is very important. But I would also want to know more about the emotional aspects. What did they go through emotionally at various points during the process, not only what happened to them.

Lucie: When we communicated prior to this interview, you mentioned that one of the central questions you’re exploring is whether it is ever possible to overcome the trauma of war. Do you feel any closer to reaching an answer after working for several months in the archives?

Nora: No. I mean, it’s also so individual. Like I said earlier, I think that everybody deals with it very differently. Some people, as you know, committed suicide. Some people were deeply depressed. One woman whose interview I watched was very interesting. She talked about how after the war she had a child, her first son, and how detached she felt. She felt basically incapable of showing anybody love. And that capacity to love seemed to have died the moment when she was separated from her family in the ghetto, and that was a moment when she basically became incapable of loving or expressing her love for anybody. After the war, she had a son, and she realized that she couldn’t give him what a mother under normal circumstances could give a child.

Thank you so much for your time, Nora, and for sharing your research and artistic experience with me. We are very excited to have you as part of our project and I am looking forward to hearing more about your book in 2026.