Resources

Our project is committed to creating adaptable and flexible educational resources in English, French, and other languages so that teachers can feel confident and knowledgeable teaching about genocides and mass traumas as part of the curriculum.

Many of the resources on this page are in-progress and will be updated as the project develops.

Educational Resources

The educational approach for the project involves using the graphic narratives as the foundation for creating linguistically, culturally, and educationally contextual teaching materials. This educational program connects with curricular priorities (21st century learning, historical thinking, human rights and global citizenship education), by teaching with testimony and graphic narratives of genocide.

Human Rights Education

The study of these events helps young people recognize prejudice, bigotry, and religious intolerance, and develop an awareness of the value of diversity in a pluralistic society, including sensitivity to the positions of minority groups.

The challenges and complexity of teaching about genocides, such as the Holocaust, is daunting (Foster, Pearce, & Pettigrew, 2020). Because of the enormity of the crime, educators must take precautions against overwhelming young people with statistics and imagery; while underplaying the atrocities may minimize the inhumanity (IHRA, 2019).

Unfortunately, confounding this challenge is the fact that many teachers are not confident in their knowledge of the Holocaust or comfortable with teaching controversial issues (Lindquist, 2008, 2011; Schwartz, 1990) and textbook content is often insufficient for an event as wide-ranging and complex as the Holocaust. In many cases, educators have relied on survivors, museums, and archives in order to compensate for the lack of classroom resources.

Graphic Narratives in the Classroom

Graphic narratives support the development of students’ critical and media literacy (Boatright, 2010; Hoover, 2012), critical thinking skills that are indispensable to an informed citizen (Seelow, 2010). As well, they encourage students to adopt inquiry habits, such as examining the historical events surrounding a narrative. Close reading is often required, as students have to consider the text as part of the image, the sequencing of the panels, the tension between the images and the text, and the use of gutters (Dunn, 2015, p. 259)

Additionally, reading and writing graphic narratives can be motivating for struggling students and reluctant readers. Developing multimodal literacy skills is a necessity for school and workplace success in the 21st century. The graphic narrative, as opposed to film or academic texts, allows the reader to pause and reflect, or to move backwards and forwards in the text (Hughes, King, Perkins, & Fuke, 2011).

Teaching through Testimony

Testimony interjects personal, palpable emotion into the often clinical telling of history and disrupts the flow of typical historical narratives. These eyewitness accounts give a face and a voice to victims, to which viewers can relate (Bickford, 2008; Felman & Laub, 1992).

For example, Holocaust survivor testimony places a face on a massive event and emphasizes the human, relatable stories of real people. It helps students to grasp the reality of an unreal event and history becomes imbued with emotion. Testimonies help to demonstrate the human and personal dimension of history without dramatizing the effects of historical events on survivors.

Historical Thinking

Teachers are engaging students with historical events in order to develop historical understanding and skills. Through the interrogation of historical accounts, using multiple primary sources, and reconciling different narratives, students are able to construct historical knowledge. If educators provide an unproblematic view of history or social studies education is conceptualized in this way, it serves to preclude critical thinking.

The Big Six of Historical Thinking (Seixas, Morton, Colyer, & Fornazzari, 2013) has been hugely influential on Canadian and international Social Studies curricula. Therefore, it behooves us, as educators, to encourage students to engage fully in historical thinking.

Human Rights and Global Citizenship Education

Human rights-based approach to education is a conceptual framework for promoting and protecting human rights (Stavenhagen, 2008). The United Nations Sustainable Development Group (2020) purports that rights based approach promotes social cohesion, integration, & stability; builds respect for peace and non-violent conflict resolution; contributes to positive social transformation; is sustainable; produces better outcomes for economic development; and builds capacity. This approach to education is evident in Canadian Social Studies curricula.

Study of genocide assists students think about the use and abuse of power, and the roles and responsibilities of individuals, organizations, and nations when confronted with human rights violations, while developing an understanding of the ramifications of prejudice, racism, anti-Semitism, and stereotyping in any society. It helps students develop an awareness of the value of diversity in a pluralistic society and encourages sensitivity to the positions of minorities.

This project will create freely available teaching materials designed to support teachers with limited knowledge as well as those who are skilled educators in genocide studies.

Teaching about the Holocaust

SCVN co-director Dr. Andrea Webb along with teachers from the University of British Columbia Teacher Education Program Community Field Experience have created comprehensive Holocaust educational materials ‘by educators, for educators.’

These materials draw on current classroom practices, pedagogy, and curriculum, but are designed for flexible implementation by teachers in a variety of classrooms.

Find the complete resource package here.

Connecting with Curriculum:

21st Century Learning

The 21st Century has been described as the knowledge age. In our current, technology enhanced world, communication, and information exchange are rapid. People interact with each other across political, social, and generational lines. Educators are preparing students to meet the demands for citizenship and careers in the millennium through core academic knowledge and complex thinking skills that are required for success in schooling, life, and a career in the 21st century. Many educators acknowledge that we are preparing students for a world that does not yet exist.

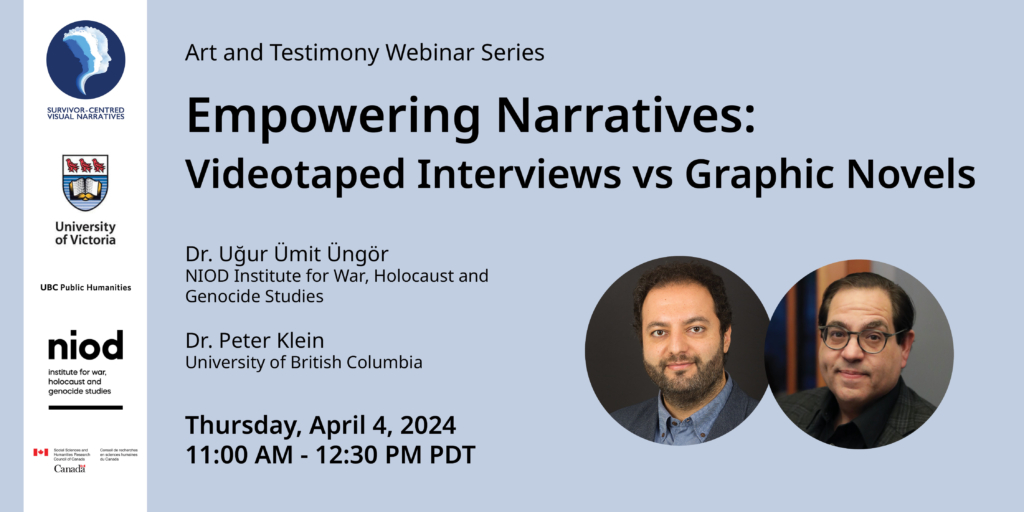

Webinars

In 2023, the SCVN project partnered with UBC Public Humanities to produce a webinar series exploring the Ethics of Trauma-Informed Research.

In 2024, we have created second collaborative webinar series on the theme of Art and Testimony that carries on these generative discussions.

Toolkits

References

Bajaj, Monisha. (2011). Human rights education: Ideology, location, and approaches. Human Rights Quarterly, 33(2), 481-508. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23016023

Bickford, D.M. (2008). Using testimonial novels to think about social justice. Education, Citizenship, and Social Justice, 3(2), 131-146. doi: 10.1177/1746197908090078

Boatright, Michael D. (2010). Graphic journeys: Graphic novels’ representations of immigrant experiences. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 53(6), 468-476. Doi: 10.1598/JAAL.53.6.3

Dunn, Kevin C. (2015). Teaching world politics with Joe Sacco: Safe Area Gorazde in the classroom (256-271). In Daniel Worden. (Ed.). The Comics of Joe Sacco: Journalism in a visual world. University Press of Mississippi. Project MUSE – muse.jhu.edu/book/40763

Felman, S. & Laub, D. (1992). Testimony: Crisis of witnessing in literature, psychoanalysis, and history. New York, NY: Routledge.

Foster, S., Pearce, A., & Pettigrew, A. (Eds.), 2020. Holocaust education: Contemporary challenges and controversies. London, UCL Press. https:// doi.org/ 10.14324/ 111.9781787355699

Glejzer, R. & Bernard-Donals, M. (2001). Between witness and testimony: The Holocaust and the limits of representation. State University of New York Press.

Harding, T. 2014. ‘Teaching the Holocaust in the “Post- Survivor Era” ’, Huffington Post, 26 January.

Hughes, J.M., King, A., Perkins, P., & Fuke, V. (2011). Adolescents and ‘autographics’: Reading and writing coming-of-age graphic novels. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 54(8), 601-612. Doi: 10.1598/JAAL.54.8.5

Hoover, S. (2012). The case for graphic novels. Communications in Information Literacy, 5(2), 174-186. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2012.5.2.111

International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance. (2019). Recommendations for teaching and learning about the Holocaust. https://www.holocaustremembrance.com/resources/educational-materials/ihra-recommendations-teaching-and-learning-about-holocaust

Lindquist, D.H. (2011). Instructional approaches in teaching the Holocaust. American Secondary Education, 39(3), 117-128.

Lindquist, D.H. (2008). Developing Holocaust curricula: The content decision-making process. The Clearing House, 82(1), 27-33.

Schwartz, D. (1990). “Who will tell them after we’re gone?”: reflections on teaching the Holocaust. The History Teacher, 23(2), 95-110.

Seelow, David. (2010). The graphic novel as advanced literacy tool. Journal of Media Literacy Education, 2(1), 57-64.

Seixas, P., Morton, T., Colyer, J., & Fornazzari, S. (2013). The big six: Historical thinking concepts. Nelson Education.

Simon, R.I. & Eppert, C. (1997). Remembering obligation: Pedagogy and the witnessing of testimony of historical trauma. Canadian Journal of Education, 22(2), 175-191. DOI: 10.2307/1585906

Stavenhagen, Rodolfo. (2008). Building intercultural citizenship through education: A human rights approach. European Journal of Education, 43(2), 161-179. 10.1111/j.1465-3435.2008.00345.x

United Nations Sustainable Development Group. (2020). 2030 Agenda: Universal values – Human rights based approach. Available https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/universal-values/human-rights-based-approach